“Honestly? I’m worried I’m next.”

The woman spoke plainly—there was no place for you-go-girl platitudes in this focus group. She’d just recounted the recent experience of watching a string of VP-level women colleagues burn out and bail on their impressive careers at her employer, sparking this moment of lucid revelation. “She saw that her company was doing nothing,” says Julie Savard-Shaw, executive director of the Prosperity Project, a charity dedicated to mitigating the impact of the pandemic on Canadian women, which had convened a discussion to hash out some of the most pressing gender-equity issues affecting workplaces today in the lead-up to its annual report card on the matter. “So, she was wondering: What is it going to take for organizations to change things, so that women don’t get to that point?”

The speaker’s comment strikes a nerve. Because a lot of women are, in fact, getting to that point.

Witness Helena Helmersson, the first woman CEO in global apparel giant H&M’s seven-decade-plus history, who cited the personal toll of leading a company through a rough run of crises in her surprise resignation, this past January: “It has been very demanding.” See Claudine Gay, the embattled first Black woman president of Harvard, taking her exit only days earlier: “These last weeks have helped make clear the work we need to do… to combat bias and hate in all its forms.” Recall Jacinda Ardern, the third (and youngest) woman to lead New Zealand, stepping down a year ago: “I have given my absolute all to being prime minister, but it has also taken a lot out of me.”

Women lead here: Corporate Canada female leadership ranked

The individual circumstances surrounding these women are nuanced and sometimes messy, but their exit remarks share a similar sentiment, of the reality of being a woman in charge not living up to the hype. If we’re having an honest conversation about gender equity in leadership, we need to acknowledge an honest truth: that when women crash through glass ceilings, they often find themselves having to navigate terrain riddled with shards—hard to see, hard to get rid of and piercingly sharp.

Is it any wonder so many are leaving—by force or by choice?

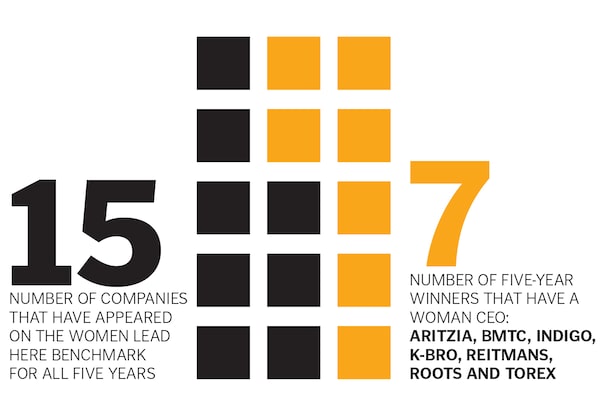

The situation is infiltrating organizations across Canada. For the fifth year, our researchers have measured the gender diversity of the top three tiers of executive leadership at the largest public corporations in Canada to produce the Women Lead Here benchmark. Upon examination of 5,500-odd positions at 534 companies, the topline is good: 26% of the executives at these businesses are women, an unequivocal improvement from 18% in 2020, when the research began. There’s a solid cohort of companies that are doing good, hard work to recruit and appoint women to big jobs—you can see 97 of them starting on page 52.

But put a cork in the pink champagne: 27% of the companies evaluated (142, to be exact) have fewer women executives now than they did last year—the highest share in five years of measuring. Put another way, more women are leaving, and being replaced by men, at more than a quarter of the biggest businesses in the country—many of which had previously been progressing toward gender equity. Most of the companies reporting declines had higher-than-average numbers of women last year; 17 had surpassed the parity threshold.

More alarmingly: The percentage of companies with women CEOs juddered down for the first time since 2020, to 6.2%, from 6.6% in 2023. Some of these were quiet exits; others, such as Rania Llewellyn’s abrupt departure from Laurentian Bank in October, were anything but. Whatever the reason, if the trend holds, by this time next year, there will be more CEOs named Mike in corporate Canada than there will be women. (We counted.) Something is clearly getting lost between companies’ desire to diversify their leadership ranks and their ability to foster conditions in which women stick around.

We may be a few years past the #GreatResignation workplace-trend hype cycle—the zeitgeist having moved on to its #LazyGirlJobs era, which doesn’t quite apply to those with executive ambitions. But for a lot of women leaders, the vibes are most definitely off. Women have always been more likely to be fired or resign from big jobs, and the shifting sands of post-pandemic work seem to be accelerating things. The most recent Women in the Workplace report by LeanIn.org and McKinsey & Co. showed women leaving positions of power at a higher rate than men in similar roles; the higher a woman sits in the org chart, the more likely she is to leave.

Celeste Woods/The Globe and Mail

A decade-plus after Sheryl Sandberg implored us all to lean in, how did we get here?

One way of interpreting the current exodus is to prejudicate: that being an executive is a gruelling gig. That some people aren’t cut out for the grind. That some people biff it on the big stage. That some people simply have different priorities. This is, of course, all true—sometimes. But when it’s a woman leaving a high-powered role, too many people link it to some innate inadequacy—a failure of temperament or resilience or chutzpah that, miraculously, hid throughout the disproportionately rigorous vetting process that got her the job in the first place—instead of looking at the bigger picture. “People are so quick to say, ‘She wasn’t strong enough’ or, ‘She effed up,’” points out Savard-Shaw. “But maybe she didn’t have the support she needed; maybe it’s no wonder she was unable to continue. If we actually talked about some of the reasons, then it might provide an opportunity for us to see it differently.”

So, let’s talk about some of the reasons. Because in 2024, being a woman in a position of power is the corporate equivalent of Ginger Rogers having to do everything Fred Astaire did, only backwards and in heels. (If that woman is also racialized, disabled, or part of a religious, cultural or sexual-orientation minority, toss a knapsack full of rocks on her back as she does it.) Most women leaders feel near-constant pressure to show their work and prove their worth; their days are filled with tiny, often subconscious, slights from those who question their competence. When things go wrong, they tend to have less leeway, less time and fewer resources to set things right. Many—if not most—have to shoulder the bulk of family caregiving responsibilities. And for all that, they’re still paid less than men. So they stress out, burn out and—more and more—peace out.

When this happens, it naturally affects the women involved: Rightly or wrongly, the stink of an unfulfilled mandate can linger like bad perfume, and women are far less likely to “fail up” than men. It also affects their organizations, which often lack the sufficiently diverse talent pipelines needed to quickly and effectively fill a vacancy with an underrepresented replacement. Furthermore, to zoom out, it affects the overall cause of gender advancement, as talented younger women see their mentors and heroes ground down and start to think, Wow, that’s not for me.

All of this sits at uncomfortable odds with the general discourse surrounding workplace equity and inclusion today. On paper, virtually every public company in Canada is a crusader for gender diversity; you likely encountered many earnest LinkedIn posts to that effect on International Women’s Day. (They kind of have to be, due to the “comply or explain” disclosure requirement added to the Canada Business Corporations Act in 2020.) By now, most CEOs and board members know that more equitable gender representation is good for business—and not only in a Will-Ferrell-in-Barbie, “I am the son of a mother, and the nephew of a female aunt” sense.

“We know that diverse leadership teams have better team outcomes, better productivity, higher job satisfaction, greater creativity and innovation. We have all of the data. We have all of the research. We know all this,” says Julie Cafley, executive director of Catalyst Canada, the Canadian arm of the global non-profit focused on building better workplaces for women. Yet, deep-seated biases and sexism don’t change overnight, so we find ourselves in a situation where well-meaning ideals are coming up against cultural and infrastructural environments that are years (or decades or centuries) behind: “The job now,” Cafley says, “is to look at these errors within the system that are consistently holding women and racialized individuals back.”

The problem with errors in the system is that they’re not obvious unless you’re looking for them.

For a long time, the idea was that companies could simply hire their way to parity. There’s a logic to it. Our economy is built on quantifiable things that fit neatly into spreadsheets—quotas achieved, deadlines met, budgets hit—and recruiting fits that bill. A company can easily measure how many women it has appointed and declare it a job well done. So, that’s where many concentrate their efforts.

“Hiring is easy because it is measurable,” says Sarah Saska, co-founder and CEO of diversity, equity and inclusion consultancy Feminuity. “Companies tend to go on these expensive recruitment shopping sprees to bring in women so they can have a splashy announcement or so they can hit the targets their board sets. And then they wonder why the women don’t feel supported or why it doesn’t work out super-well.”

All corporations carry the baggage of their history, and since most of history was pretty sexist, vestiges of bias and discrimination tend to cling to a company’s policies, systems and processes long after it has declared its commitment to gender equity. Even the most progressive and well-meaning organizations are likely to find evidence of what researchers call “benevolent sexism” if they look closely enough.

Sometimes, this takes the form of good initiatives that fall flat in the execution. A company might launch a mentorship program, for example, to provide talented women with support and connections. Great! But do they follow up to track who’s actually using it and who’s not? Do they equip mentors to use their clout to advocate for their mentees and sponsor their progression? Or a business might offer a generous parental leave top-up. Admirable and important! But how many women are taking it? How are they talked about in conversations about potential and advancement? And are those who opt out rewarded? “It’s important to question how policies are being applied and implemented,” says Carmina Ravanera, senior research associate at the Institute for Gender and the Economy at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. “You can have a no-tolerance policy toward something like harassment, and you can encourage reporting and accountability, but what happens when someone reports something? Are they penalized or supported? You need to pay attention to what is actually happening on the ground.”

Sometimes it’s a matter of scrutiny. Yes, every leader should be held to account. Yet if we learned anything from Barbie, it’s that perfection is a myth, so to hold women leaders to disproportionately high, often contradictory standards for everything from their accomplishments (which must be substantial but never bragged about) to their comportment (which must be authoritative but never cold) and yes, their appearance (which must be polished but never flashy) is both bogus and sad. And even when women do get it right, their colleagues are more likely to downplay the achievement than celebrate it. “When women succeed—when they get that promotion or take public-facing roles or whatever it is—they get cut down,” says Rumeet Billan, owner and CEO of Women of Influence+, whose research has found that 87% of working women have experienced what’s known as “tall poppy syndrome” in their professional lives. “We need to shift from women having to cope with criticism to actively challenging it and changing the systems that perpetuate it.”

Sometimes, the problem lies in workplace cultural expectations that reinforce a stereotypically male version of leadership. An awful lot of deals still get done on the golf course or at a hockey rink, and while of course women can and do participate in such activities, a quick scan of the corporate boxes at any Leafs game will reveal who’s included—and who’s not.

And sometimes it’s a matter of unintentional, force-of-habit disrespect. According to the 2023 McKinsey and LeanIn report, women are twice as likely as men to have to deal with common microaggressions (that is, subtle and demeaning digs), making work a “mental minefield.” Think of the woman expected to get coffee and snacks for the meeting she’s chairing, or the one whose ideas are routinely talked over in strategy sessions, or the one who’s considered overly emotional for defending a position, or the one who’s asked “Who’s taking care of your kids?” with a whiff of incredulity.

Are you tired yet? This stuff is tiring.

But it’s all there, more often than you might think, if you start looking beyond just what you want to see.

And look, it’s no fun: No executive wants to believe that their good intentions aren’t translating, and most would be horrified to know their blithe behaviour is contributing to a toxic workplace. But just as you can’t wish yourself a smash new product or dream your way out of a recession, you can’t confirmation-bias your way to an equitable organization. “It’s hard work to look in the dark corners and to have real conversations about what you see,” says Saska of Feminuity. “But it’s only when organizations really dig in and deal with their issues that everybody has a better shot of having a good day-to-day experience in the workplace.”

Lest this read too much like homework: There’s a great upside to all of this. Once companies go through the uncomfortable work of reckoning with what their women leaders really experience, and once they change that which must be changed accordingly, they’ll find more of those women leaders stick around to do great work. They’ll build stronger talent pipelines, improve the whisper-network raps they may or may not know about, and better live up to the gender-equity ideals they espouse.

There’s reason to be optimistic, says Jodi Kovitz, CEO of the Human Resources Professionals Association and a longtime advocate for corporate gender diversity. She’s witnessed a “mindset shift” that—paired with momentum—holds the potential to drive real change. “If we’re interested in fostering, like with a very capital F, a culture of inclusion, and really enabling a culture that allows folks to be successful, our energy needs to be invested in weaving these ideas—this mindset shift—into the DNA of our companies,” Kovitz says. “There has been a lot of progress, but we must not stop. Because the second we take our foot off the gas is the second we start to go backwards.”

Laura Dottori-AttanasioAngela Lewis/The Globe and Mail

Make it a team effort

Laura Dottori-Attanasio, President and CEO, Element Fleet Management

Dottori-Attanasio is a Bay Street star who left her role as CIBC’s head of personal and business banking (where she was considered a potential successor to CEO Victor Dodig) in early 2023 to take the top job at Element

“In my experience, sponsorship, mentorship, collaboration and advocating for diversity, inclusion and belonging have all been crucial factors in creating a more equitable workplace. Organizations like Women’s Executive Network, formal company-sponsored mentor programs and employee business resource groups have all provided access to a supportive network of mentors, colleagues and advocates who have been instrumental in my career progression.

These resources and individuals have offered guidance and encouragement, helping me navigate through various obstacles and opportunities. I am grateful for their support and believe that having a strong network is crucial for any leader’s success.

I think it’s important to be self-reflective. What’s been your lived experience? What would you have wanted to be different to enable your own personal growth, development, or career satisfaction?

We all need to work together toward a future where everyone can thrive. Regardless of gender, I believe that when we focus on diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging, everyone benefits. It’s important that we continue to make strides toward creating more equitable and inclusive environments so that everyone can reach their full potential.

It really comes down to empowering others and our greater responsibilities as leaders. As leaders, we have the power to influence and shape the companies we lead, and the communities where we work and live. It is our responsibility to use this position to drive real, sustainable change. Sometimes this is leading the change; other times, it is amplifying other voices and giving them an opportunity to shine. It’s all about bringing people along and creating opportunities for others to grow and move the dial.”

Andrea LimbardiPam Lau/The Globe and Mail

Normalize realistic expectations

Andrea Limbardi, CEO, Reitmans Cos.

Limbardi is a retail veteran who climbed the ranks at Indigo—most recently to president—before quitting in 2023, amid management chaos at the book chain, to become the first non-family CEO at Reitmans

“I‘ve had a lot of support over the years. Having a group of people who you can count on to give you real advice and real perspective— not just to be cheerleaders, but really tell you what’s hard to hear—is critical, and I’ve had that my whole career. There are people I worked with 30 years ago who I can still count on for a real perspective.

I think knowing that you’re not able to do all things yourself is really critical. As women, in particular, we put this weight on our shoulders that we should be good at everything. I’m really bad at a lot of things and I’m good at a lot of things. I know what those things are and how to surround myself with people who are smarter or better than me in the areas where I’m not, and to stay in touch with those people and to surround myself with those people on my team in my external network.

I’m also a mother of a young child. My son’s six; it’s just not possible to do it all. So I think the best example we can give to others, and to our children, is by being really honest about that. Because everyone feels that pressure.”

I believe in giving an incredible amount of trust to the people on my team. You have to give them the autonomy to be successful and be there to help them by removing obstacles—not by micromanaging. They need to know that they can make mistakes, and know that they have support. As senior leaders, we have to give space for people to be successful. That’s just so critical.”

Anthea BathAngela Lewis/The Globe and Mail

Encourage women to be themselves

Anthea Bath, President and CEO, Wesdome Gold Mines

Bath’s CV is stacked with senior roles at energy and mining firms, including at Vancouver’s Ero Copper, where she was COO before becoming Wesdome’s CEO in 2023

“I encourage companies to come to diversity from a place of true understanding. In some cases, I don’t think organizations truly believe in the value that diversity can bring. I sometimes wonder if it’s something they do because they have to. Do they understand why a board conversation is so good when you have women there? Do they understand what having differences in leadership teams brings?

A woman’s style does not necessarily correlate to a typical business style. I’m in mining, which can still be pretty macho. My style has an authenticity about it, which I love, but it can be difficult for people to understand. I don’t know how many conversations I’ve been in when I think to myself, Would this person say this if I were a man?

I encourage women to be their authentic selves, because it’s in the authenticity that you’re going to get their best out of them. And I encourage leaders to talk to women to understand what is going to work for them as individuals. When you really listen to a woman—to really understand her and the influential person she can be—you’ll start to see what she can do.

Most of the women I know who have been treated with respect and kindness give 20 times more. When a woman feels she can be herself—when she feels safe to be who she is—you’ll be surprised at the value you get out of it.”

Samira SakhiaPam Lau/The Globe and Mail

Recognize what your leaders really need

Samira Sakhia, President and CEO, Knight Therapeutics

“As CEOs, we need to recognize that different people have different experiences. For example, a lot of people have been educated and trained to ask for more. But a lot of other people—and a lot of minorities—have not been trained to ask for more. As a leader, you need to recognize that difference. Some people are going to come to you with what they want, and it’ll be easy. For others, you’ll have to pull it out of them or push it on them. You have to be thinking of these things.

As our company grows, we’re more open to continuously rejigging the structure of the leadership team to keep work sustainable. Last year, we split the role of one senior leader in two. The job had grown to the point that it was getting to be too much. It brought her a huge amount of relief and took a lot of stress away. Some of these changes are comfortable. Some are not. But we’re working together to get there.

We’ve all seen examples of women saying something, and then someone else saying very similar words five minutes later and getting the credit. That happens all the time, and it almost defeats the purpose of having that woman in the room. As leaders, we have to consciously listen and hear and acknowledge that we’ve heard. We need to show our respect that they’re in the room, and we value their opinion. It’s not always something leaders are used to doing. But if I can do it, when I never had to for 30 years of my career, anyone can learn.”